The Dream You Can’t Share

© Dave Needham

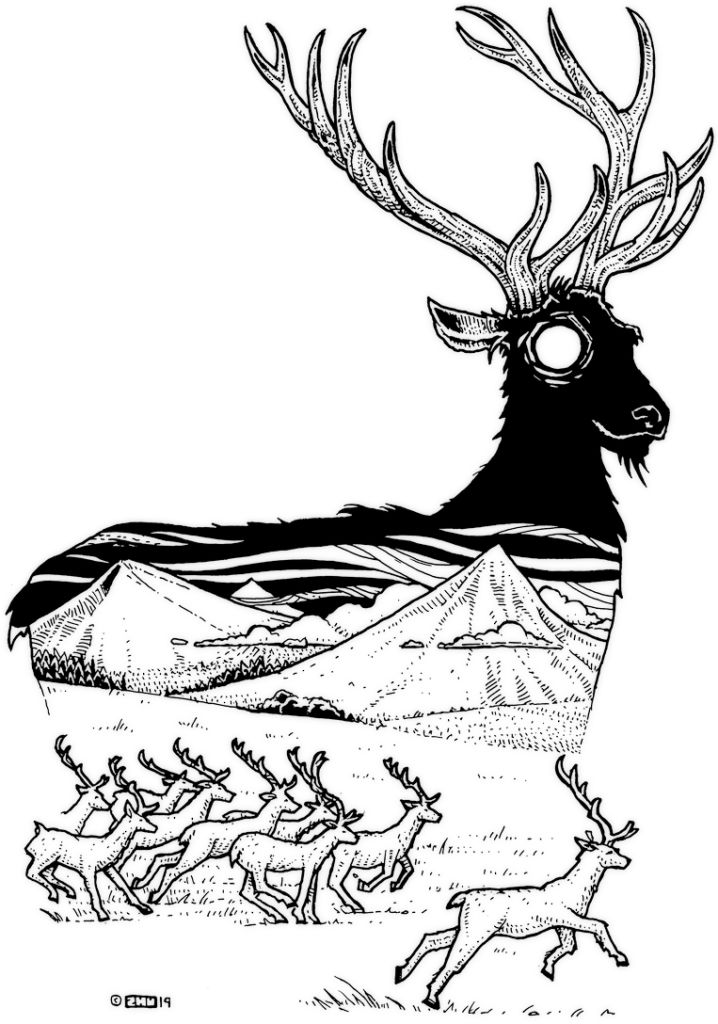

Illustration for the 81st case.

I want to talk today about something I rarely mention in my dharma talks: Enlightenment, or the Buddhist idea that meditation leads you to a sort of awakening into your true nature.

One of the strange ironies of our practice is that many people come to meditation because they wish to find a new way to deal with their anxiety. Mindfulness meditation, for example, is often taught now, by psychologists and therapists as a way to cope with anxiety and other persistent emotions. And, there’s excellent evidence, both from scientists and practitioners, that meditation can make you less anxious.

However, back in China, Korea and Japan, where Zen originates, meditation isn’t a path toward alleviating anxiety, but a path towards causing it.

Traditionally, Zen practitioners don’t meditation on their breath. They meditate on a koan (a short phrase or story) by repeating it silently hundreds or thousands of times a day. These koans may be simple questions like “What am I?” or something more elabourate like my old koan “Everything returns to the One, what does the One return to?” Recently I got a post-card from my Zen Master informing me that he had just had an Enlightenment experience and that he was changing my koan. It’s funny that his experience changes my koan, but we are interconnected that way. My new koan is “Cross the ocean, ride dead body.”

Anyway, the point isn’t to figure out what the answer to the koan is or what it really means. Koans are designed to be unanswerable, like knives are designed to sharp.

The point of meditating on a koan is to spend weeks, months or years beating your head against it. It’s meant to make you anxious and frustrated. The great Japanese teacher Hakuin called this deep feeling of intolerable unknowing “the ball of doubt.” The ball of doubt is not pleasant. Hakuin taught that a meditator should generate a ball of doubt so painful that it sits in your throat like a lump of molten bronze. It’s so big that you can neither swallow it nor spit it out. He wrote, “This is just like a deaf-mute who, although he dreams, still only knows of it himself, and cannot tell it to anybody.”

What’s the purpose of all this angst? Well, the idea is that you create all this tension in your gut until your mind can’t handle the pressure anymore and the dam breaks and you are washed away. That rupture is Enlightenment. As Hakuin said again, “And so suddenly if the Koan is broken, a vigor that shakes heaven and earth is produced. This is just as if you snatched the great sword away from the God of War and used it to kill the Buddha.”

Let’s go back to my own Zen Master. He told me an interesting story once about his own quest for Enlightenment. When he was a young monk, shortly after the Korean War, he was having trouble making progress in his meditation. So his Zen Master, who lived near Seoul, sent him to the south of the country to study at a different monastery. There Sunim, my teacher, practiced and practiced, cultivating the molten ball of doubt with more and more anxiety. Finally, one day, he snapped. Pow! He had a realization: a luninous understanding of his true nature. Finally, finally, it has happened to him!

He has to share this with his teacher. He has to keep his understanding pristine and prove that he’s become enlightened. But it’s just after the war, and the country, the roads are in ruins. There’s no Greyhound Bus. So he sets off on northwards on foot. He crosses rivers and mountains. Trying not to sleep, trying not to talk to anyone for fear of disrupting his perfect view. He has no idea how long he walks for — the whole time passes like in a dream. And eventually he reaches his teacher’s monastery. At this point Sunim looks like a hobo – he’s dirty and smelly and his clothes are falling off his bones, but he doesn’t care. Sunim barges into his teachers private apartments, interrupts him while he’s meditating, and tries to tell him what has happened. But as soon as he looks at his teacher’s face, Sunim forgets everything. He forgets his enlightenment, forgets his insight, he forgets what he was going to say. Once more, he is like a deaf-mute dreams but cannot tell his dream to anybody. His teacher looks at him and says, “Why have you come back?” Sunim starts to mumble in response, and his teacher commands him to go back to the South and keep meditating. End of story.

What does it all mean? I don’t know. Maybe that story is like a koan itself – it’s a mistake to try to figure out what it means. All we can do is appreciate the mystery.

I will say this, however. Seeing your self-nature is always a surprising experience. We have this highfalutin view of our true selves, just like we have a highfalutin view of enlightenment. (And in fact, they are the same thing). But both won’t come in the shape or colour that we expect. Was Sunim’s true awakening in the South? Or was it in the North, when he forgot everything that he was going to say?

August 2019