Finding the Ox

© David Needham, 2019

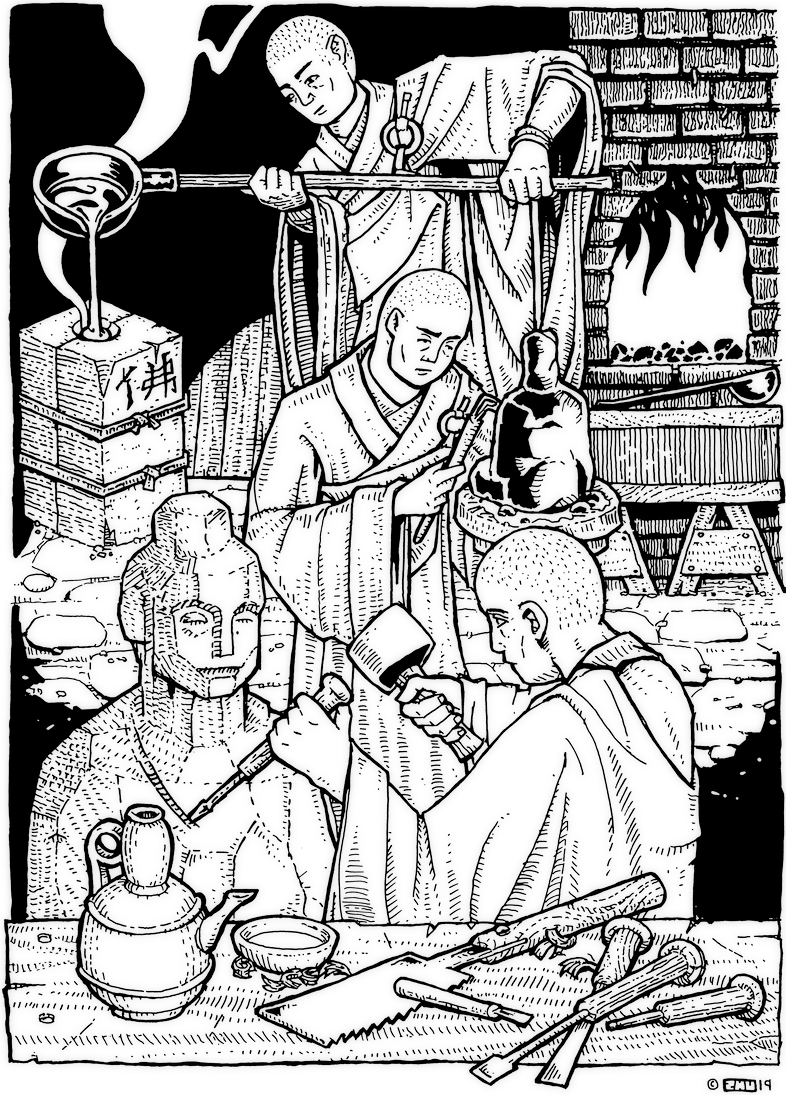

Illustration for the 96th case.

There is a saying in Zen Buddhism that meditation is like herding an ox. Starting around the 12th or 13th century, Zen Buddhists used painting, poetry and sculpture of oxen to represent the path of the meditators. The most famous of example of this are the “ten ox-herding pictures” painted by the Zen Masters of the Song Dynasty. These paintings are still used today when we teach our students about Zen meditation. In fact, the first dharma talk my teacher ever asked me to give was about the 10 ox-herding pictures.

But I shouldn’t mislead you. It isn’t only in Zen that ox herding is important. Over a thousand years before Zen began, the historical Buddha was using the idea of herding ox in order to teach his students. The early sutras preserve a charming passage where the Buddha likens a meditating monk to a diligent herdsman:

Monks: a herdsman endowed with eleven virtues is capable of looking after a herd so that it prospers and grows. Which eleven? The herdsman must understand appearances, be skilled in characteristics, picks out flies’ eggs, dress wounds, fumigate the stall, know the fords, water the herd, know the path, be skilled in pastures, refrain from milking dry, and respect the leaders of the herd. A cowherd endowed with these eleven virtues is capable of looking after a herd so that it prospers and grows.

A monk endowed with these eleven virtues is capable of attaining growth, increase, and abundance in this Dharma. Which eleven? The monk must understand appearances, be skilled in characteristics, picks out flies’ eggs, dress wounds, fumigate the stall, know the fords, water the herd, know the path, be skilled in pastures, refrain from milking dry, and respect the leaders of the herd. A monk endowed with these eleven virtues is capable of attaining growth, increase, and abundance in this Dharma.

The Buddha goes on to explain what he means by picking out flies eggs or not milking the udder dry — all of these things are metaphors represent good habits that the meditator must develop in order to grow in the Dharma.

But Zen Buddhism, 2000 years later, made a small but important improvement on the Buddha’s teaching — and that’s what I’ve been mulling over for the past month. The Zen poets and painters agreed that meditation is like herding an ox, but they pointed out that before you can herd that ox, you have to find it.

And so, in those Ten Ox-Herding paintings, the first three pictures are all about finding the ox: The first is called “In Search of the Bull,” the second “Finding the footprints,” and the third “Catching Sight of the Ox.”

What is the ox? Your mind is the ox. It’s big and magnificent and powerful, but also wayward and a little stupid. And the great insight of Zen is that you can’t tame your mind before you actually catch sight of it in the first place.

This is quite a surprising thing to say. Most of us just sort of assume that we see our own minds all the time. After all, we spend most of our time thinking thoughts and thinking about our thinking. It’s easy for us to take for granted that all this thinking is our mind. In fact, when I teach my meditation classes, I usually hear one or two people say “I can’t meditate because I have too many thoughts.” These people don’t think their problem is that they can’t find their mind — they think their problem is that they can’t lose it!

Not so fast, says Zen. That assumes that your thoughts and your mind are the same thing. But is that really true? Where are your thoughts before you think them? Where do they go after they are done being thunk? What is the space in between the thoughts? What is there when there are no thoughts at all?

Or let me put it another way — what colour is your ox? What sound does it make? What do its footprints look like? How do you catch sight of it? When you see it, how will you know that it’s really an ox and not a log or a shadow?

I don’t intend to answer any of these questions. And, of course, I’m completely incapable of doing so. That is because no one can point out your ox to you. You have to look for it yourself, find its own unique set of tracks, and find it on your own. Not that you are alone… when we sit together in meditation, we are all helping each other, like herdsman calling to each other from one hill to another.

So when you sit in meditation, and rest your mind on your breath, and become distracted and let go of thoughts, you are really calling out for your ox. Please meditate and find out what happens when you find it.

March 2017